Obras de referência da cultura portuguesa

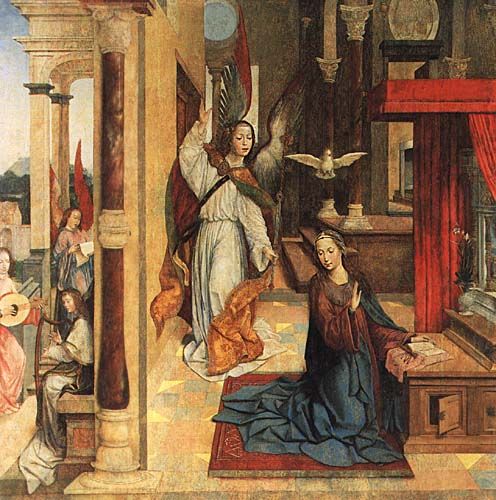

"ANUNCIAÇÃO"

de FREI CARLOS

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisboa

Análise de Rui-Mário Gonçalves

Tradução: Paul Bernard

O anjo anuncia à Virgem Maria que ela será a mãe do Filho de Deus. Um dos seus braços está na direção do Céu, de onde ele vem; o outro baixa-se, em direção a Maria. O Espírito Santo está presente, representado pela pomba branca, na vertical acima da cabeça de Maria, sendo esta verticalidade subtilmente marcada por uma coluna, ao fundo. As verticais desempenham um papel fundamental nesta composição: sublinham o movimento do anjo, que vem do alto e da luz. O anjo parece não ter peso: mal está pousado e as suas roupagens ondulantes indiciam o seu movimento. Ele é a personagem mais ativa, portadora da decisão divina. A verticalidade do seu vestido contrasta com a horizontalidade de grande parte do manto da Virgem, bem assente no chão. Dourado, branco sombreado com azuis e vermelho são as cores das vestes do anjo. Azul e vermelho são as cores, respetivamente, do manto e do vestido da Virgem. O vermelho é a cor da nobreza. Essa cor aparece em todas as figurações de Maria, para indicar que ela pertencia à genealogia dos reis, da Casa de David. Outros atributos dela são: o recato do espaço interior, onde domina a cor vermelha, o livro de orações e os lírios, símbolo de pureza. Como geralmente acontece nas pinturas narrativas, a ação desenrola-se da esquerda para a direita, ou seja, a parte mais agitada fica à esquerda da composição, reservando-se a parte da direita para quem é destinatário da ação, geralmente a personagem mais importante. A Virgem, ajoelhada, ouve o arcanjo Gabriel, baixa modestamente os olhos e ergue a mão à altura do peito em sinal de obediência e compromisso.

O quadro é da autoria de Frei Carlos, pintor de origem flamenga que em 1517 se tornou monge hieronimita em Évora. Não se conhece a data do seu nascimento, nem a da morte. Integrou-se na Oficina do Espinheiro e a sua arte fez uma admirável síntese entre o estilo de Bruges e o dos portugueses. No primeiro caso, deve reparar-se no azulamento das montanhas longínquas, modo através do qual os pintores nórdicos iniciaram a construção da perspetiva cromática, baseada na observação do mundo real; deve também reparar-se no gosto de ornamentar todo o espaço próximo com colunas de ónix, tapete e reposteiro vermelhos, criando um ambiente solene propício à subtileza teatral dos gestos das personagens, com os seus rostos elípticos alongados e dedos afilados. Quanto à bipartição da cena, distinguindo o espaço interior e o exterior, onde os anjos festejam com música o ato iniciador da redenção da humanidade, pensam alguns historiadores que ela pode ter afinidades com o tipo de cenografia utilizada por Gil Vicente. A bipartição, sendo acentuada por uma coluna no primeiro plano, é todavia unificada pela perspetiva linear, cujo ponto de fuga se encontra cerca do rosto do Arcanjo Gabriel, fazendo portanto convergir para ele o olhar do observador do quadro. Esta perspetiva é rigorosa nos ladrilhos do chão e torna-se enfática na escadaria representada atrás da figura da Virgem. Pelo contrário, a iluminação é pouco marcada, quase não havendo sombras projetadas, o que facilita a integração das figuras no plano pictural, tornando-as perfeitamente legíveis. O predomínio das verticais sobre as horizontais faz esquecer o peso dos corpos. Tudo levita nesta suave composição quadrada. O seu centro é a mão do anjo que empunha o báculo transparente no momento da anunciação: Ave Gratia… Estas palavras aparecem transcritas no bordo dourado das vestes do anjo.

“ANNUNCIATION” (1523) by FREI CARLOS

National Ancient Art Museum, Lisbon

The angel announces to the Virgin Mary that she will be the mother of the Son of God. One of his arms is raised towards Heaven, from which he has come; the other is lowered, in the direction of Mary. The Holy Spirit is present, represented by the white dove, in a vertical position above Mary’s head, and this verticality is subtly marked by a column in the background. The verticals fulfil a fundamental role in this composition: they underline the angel’s movement, coming from on high and the light. The angel appears to be weightless: he barely rests and his wavy clothing indicates his movement. He is the most attractive of the figures, being the bearer of the divine decision. The verticality of his clothing contrast with the horizontality of a large part of the Virgin’s cape that rests well on the ground. Gold, white shadowed with blues and red are the colours of the angel’s clothing. Blue and red are the colours, respectively, of the cape and dress of the Virgin. Red is the colour of the nobility. This colour appears in all the figurations of Mary, to indicate that she belonged to the genealogy of the kings, of the House of David. Other of her attributes are: the seclusion of the interior space, in which red dominates, the prayer book and the lilies, a symbol of purity. As usually occurs in narrative paintings the action develops from left to right, or if one prefers, the more active part is on the left side of the composition, with the right being reserved for the person towards whom the action is directed, generally the most important person. The Virgin, kneeling, listens to the archangel Gabriel, she modestly lowers her eyes and raises her hand to her chest as a sign of obedience and commitment.

The painting is the work of Frei Carlos, a painter of Flemish origin who in 1517 became a Hieronomyte monk in Évora. The date of his birth, just like the date of his death, is unknown. He was part of the Espinheiro Studio and his art made an admirable synthesis between the Bruges and Portuguese styles. In the former instance one should notice the bluing of the distant mountains, a means by which northern artists began the construction of the chromatic perspective, based on observation of the real world; one should also notice the taste for decorating all of the nearby space with onyx columns, a red carpet and drapes, creating an atmosphere propitious to the theatrical subtlety of the characters’ gestures, with their elongated elliptical faces and slender fingers. As for the bipartition of the scene that distinguishes the interior and exterior spaces, where the angels feast with music the initiatory act of the redemption of humanity, some historians believe it may have affinities with the type of scenography used by Gil Vicente. The bipartition, emphasised as it is by a column in the foreground, is still unified by the linear perspective, whose point of departure may be found close to the face of the Archangel Gabriel, thus drawing to it the eye of the observer of the painting. This perspective is rigorous in the floor tiles and becomes emphatic in the staircase represented behind the figure of the Virgin. On the contrary, the illumination is little marked, with virtually no shadows being cast, which facilitates the integration of the figures on the pictorial plane, making them perfectly legible. The predominance of the verticals over the horizontals makes one forget the weight of the bodies. All levitates in this smooth square composition. Its centre is the hand of the angel that grasps the transparent crosier at the moment of the annunciation: Ave Gratia... These words appear transcribed on the gold hem of the angel’s clothes.

Obras de Referência da Cultura Portuguesa

projeto desenvolvido pelo Centro Nacional de Cultura

com o apoio do Ministério da Cultura

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos