Quarteirão das Artes

For the plot

The Medal of Good Intentions, The Medal of Good Works, The Medal of Sacrifice, The Medal of Blind Obedience

16 Jan a 31 Jan 2026

It is from this tension that artist Luzia Cruz begins her first solo exhibition at Mono in Lisbon. Drawing inspiration from Fiama Hasse Pais Brandão, a writer censored during Portugal’s Estado Novo dictatorship, Cruz connects to Brandão’s never-performed play The Will to uncover a moment that never reached the public. Conceived as an experimental play-within-a-play, it staged the social dynamics of its time while questioning structures shaped by colonial history and Christianity. It was censored a year after publication and never performed. What remains is a text separated from the audience it was meant to address, a story suspended in an incomplete state.

Cruz observes the intervals between these unfinished moments, those that hold the potential to form a storyline and the ways they disseminate into different registers. These become third spaces that inhabit the imaginary and collective beliefs, supported by values that give any plot its backbone and the possibility of becoming real or not. The analogy of theater becomes essential as she examines the boundaries of storytelling. As Ursula K. Le Guin might argue, every story becomes a collection, a bag of selected narratives, a composite of what society chooses to repeat.

As decolonization brings forth narratives long overshadowed, an entropy of realities emerges. Sylvia Wynter opens Novel History, Plot and Plantation by stating, “These things that happen... It is best to call them fiction.” She examines the values and consequences embedded in stories and highlights the failures of historicization, where authorship becomes crucial. In the context of the plantation, history becomes fiction. Wynter writes, “It is only when the society, or elements of the society, rise up in rebellion against its external authors and manipulators that our prolonged fiction becomes temporary fact.” Truth becomes temporal, sustained only as long as a play is performed, as long as a book is read, as long as it remains unquestioned.

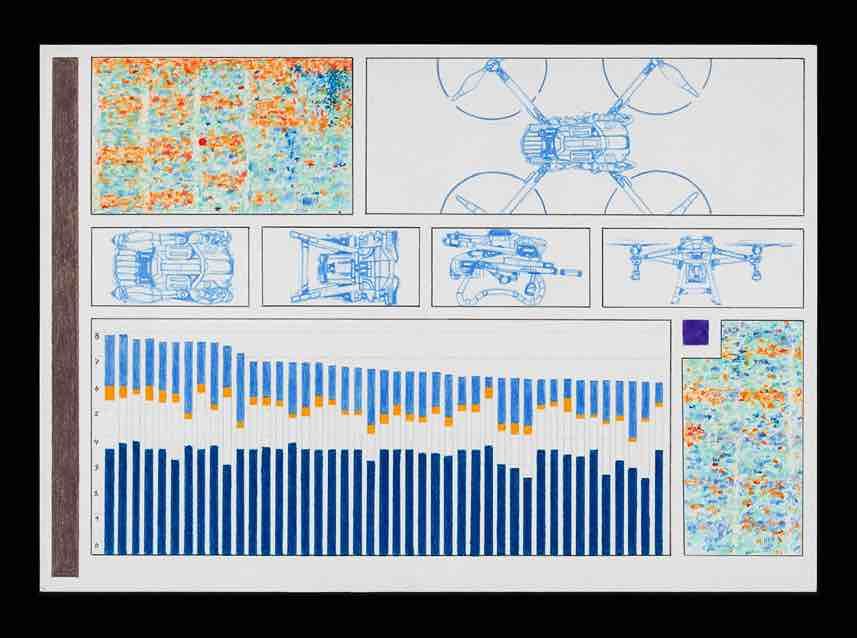

In her artistic research, Cruz focuses on the narration of progress. She begins by tracing the logic behind technological production and the promises of advancement, paralleling what Wynter describes as colonial extractivist modernity, a form of fictioning in which systems of production remain grounded in exploitation. Writing from the “crop,” as Wynter would say, she connects labor and technology, revealing how ideals of progress and hope have long been entangled with violence, from the plantation to the agricultural revolution and into the automation of drones now used to oversee fields. Technologies presented as noble instruments that feed the world and optimize resources often function as soft forms of colonialism, concealing military capacities and exploitative origins. A drone capable of spraying pesticides is equally capable of carrying weapons, both justified by the same rhetoric of advancement.

Through her work, Cruz uses theater not only as a metaphorical device but also as a way to examine the fabrication and replication of narratives, particularly those surrounding the ideologies of technological progress. Agricultural pesticides, for example, are celebrated as high-development tools for crop optimization, while the narrative omits how closely this technology resembles warfare. The story instead highlights the well-fed, content civilians, analyzed and synthesized in reports that fall under the ideal of a global “happy” society secured by progress. It remains a narration, a plot of hope.

Cruz approaches for the plot as a moment of alternative framing, opening imaginaries that do not subscribe to the storyline they have been assigned. She navigates European contexts shaped by cultural legacies. On one side is her native Portugal and the persistent influence of religion and colonial silence. On the other is Germany, her place of residence, where memory and identity remain in ongoing negotiation. She investigates how censorship and political systems have worked to obscure colonial histories, transforming horror into honor.

The installation at Mono draws from these processes and aesthetics, examining spaces where truth never fully unfolded, as in Fiama’s censored plays. Her work lingers within atmospheres connected to manufacturing, production, and the quiet authority of technical spaces. These are environments where progress is assembled behind closed doors, where collective stories develop gaps. It is into these gaps that Cruz steps. By evoking places that resemble reliable sources of production, from factories to testing rooms where technology is standardized and later conceptualized in service of public narratives, the installation becomes a stage. Viewers bring their own knowledge to it, allowing the work to acquire a hyperreal value, the replication of reality within reality.

for the plot juxtaposes familiar moments with unfamiliar information, pointing toward the proxy of progress and functioning as a shared space where collective ideologies are displayed, repurposed, and redirected in order to challenge perception. It adopts a borrowed aesthetic that performs a role, mirroring how agriculture, as a fundamental source of human sustenance, becomes a metaphor for manufacturing itself. Throughout history, both have been shaped in service of economic interests. As Wynter notes, “In the world of use value, human needs dominate the product. In the world of exchange value, the product, the thing made, dominates and manipulates human needs.”

Does ideology always underpin the promise of something better? Does economic liberation justify the means required to obtain it? Has the promise of modernity always been flawed? The exhibition invites a reconsideration of the mythologies and refined aesthetics surrounding milestones of advancement, as well as the stories of exploited land and the reconfiguration of labor conditions shaped behind closed doors and later presented to the public in clinical aesthetics of polished pedestals: THE MEDAL OF GOOD INTENTIONS, THE MEDAL OF GOOD WORKS, THE MEDAL OF SACRIFICE, THE MEDAL OF BLIND OBEDIENCE.

The Campaign, Fiama Hasse Pais Brandão

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos